Seizures in Dogs

Seizures, which are sometimes referred to as convulsions or fits, can occur in dogs for many different reasons. Idiopathic epilepsy is the most common cause. A seizure occurs when the brain's cerebral cortex functions abnormally, leading to unusual behaviors or movements. The cause of this malfunction may be a physical abnormality, toxic exposure, trauma, or disease. While any breed of dog can have a seizure, certain breeds, including German shepherds, beagles, huskies, Akitas, and Labrador retrievers, are prone to epilepsy.

What Is a Seizure?

A seizure is a symptom of a neurological disturbance in a dog's brain. There are many causes of seizures, ranging from anatomical to environmental, but all result in a temporary disruption of the normal electrical impulses within the dog's brain. The presentation of seizures ranges from a momentary lapse in consciousness to full-blown physical convulsions.

Status Epilepticus

A prolonged seizure (over five minutes) or a series of seizures that occur in rapid succession is called status epilepticus. This is a medical emergency. If left untreated, this type of seizure can lead to brain damage, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), and death. Dogs in status epilepticus require hospitalization and may need a constant infusion of medication to stop the seizures.

Symptoms of Seizures in Dogs

There are three phases of symptoms that characterize seizures, as follows:

- The pre-ictal phase: Your dog may sense that something is not quite right before a seizure occurs and behave strangely (pacing, whining, carrying rocks or toys, running into walls or furniture, or acting lethargic). Also called the prodrome, this phase can last a few seconds up to a couple of days, and symptoms tend to be subtle, so you might not be aware that anything is amiss.

- The ictal phase: This is the stage you will likely notice and classify as a seizure, regardless of severity. Your dog may show a lapse in consciousness, stare into space, run in circles, or convulse. This phase can last anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes and is considered the active phase of the seizure.

- The post-ictal phase: This phase may last minutes to hours. Aside from profuse panting, symptoms can be subtle and might go unnoticed. After the seizure, a dog may seem listless or depressed. Alternatively, some dogs appear restless and pace incessantly for a while. This is called the post-ictal period and the length of recovery can be quite variable.

During the ictal phase of a seizure, symptoms manifest as abnormal motor (movement) symptoms, abnormal behavioral symptoms, or a combination of both. The following symptoms are common but may be alarming:

At the first sign of a seizure, it is important to make sure your dog is in a safe place where it cannot hit its head or fall while experiencing potentially violent, jerking movements. Keep your hands and face away from your dog's mouth during the seizure because your dog can't control its movements and may bite you unintentionally.

If your dog has recurrent seizures, you will likely become accustomed to the "routine" of quickly moving your dog to a safe place (if possible) and having paper towels on hand to clean up drool, urine, and feces.

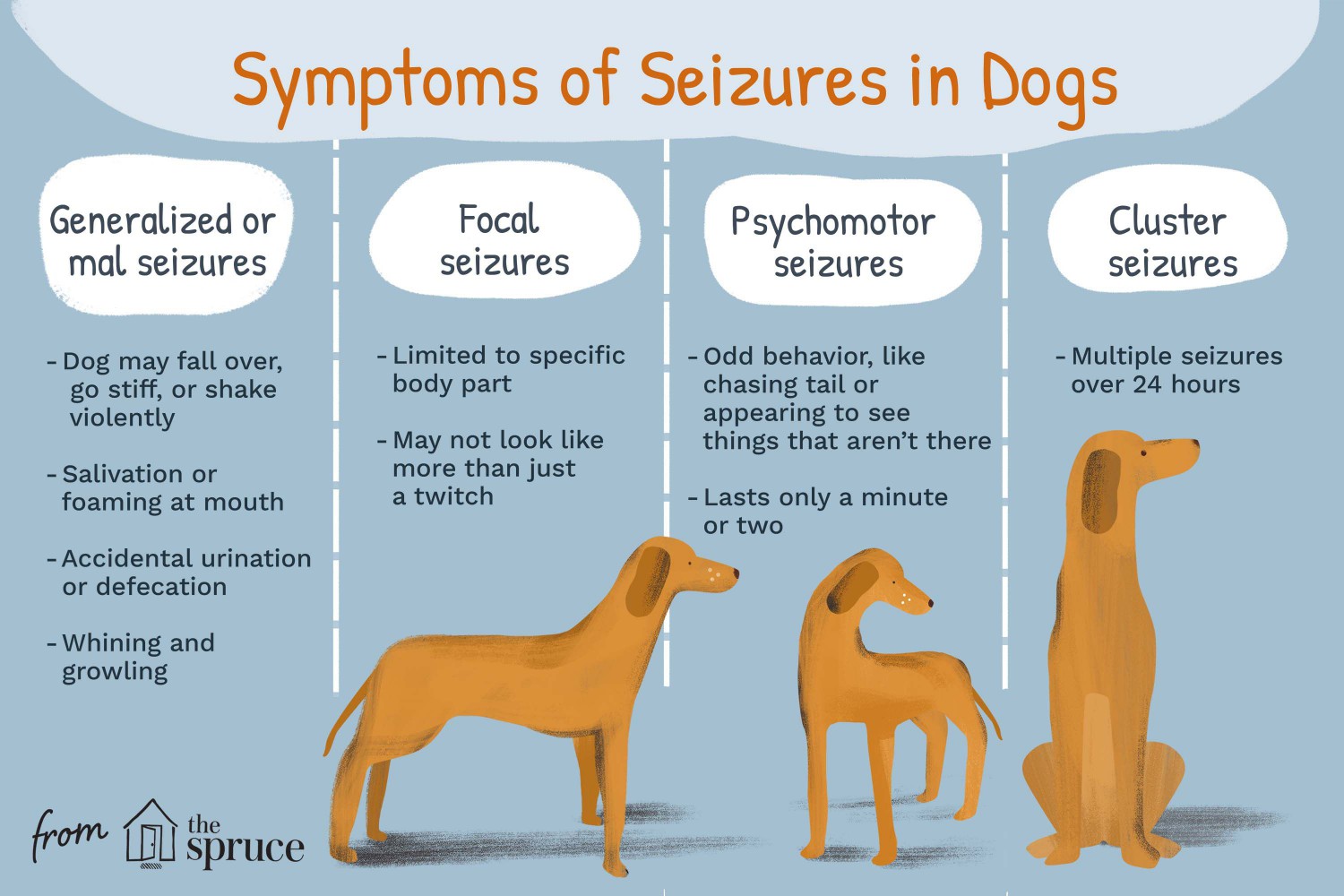

Illustration: The Spruce / Michela Buttignol

Grand Mal Seizures

These are generalized motor seizures that involve the entire body. A dog suffering a grand mal seizure may fall over, become stiff, and shake its whole body violently. Many dogs salivate or foam at the mouth, and some urinate and/or defecate involuntarily. Dogs may vocalize as well, whining and growling during a seizure.

Cluster Seizures

Clusters are serious seizures, distinguished by multiple grand mal seizures over 24 hours that may occur in rapid succession, increasing their severity and the risk of experiencing status epilepticus.

Psychomotor Seizures

Psychomotor seizures are characterized by odd behavior that lasts only a minute or two. For example, your dog may suddenly start chasing its tail or acting as if it sees things that aren't there.

Focal Seizures

The least serious type, these seizures are limited to a specific part of the body and may not look like much more than a twitch in the dog's facial muscles or limbs.

Causes of Seizures

Seizures have different causes, and various external influences can trigger seizures in susceptible dogs. The common causes of canine seizures include the following:

- Idiopathic epilepsy (generally considered hereditary with no known anatomical or environmental cause)

- Changing brain activity (falling asleep, waking up, or experiencing a high level of stimulation/excitement)

- Allergenic ingredients in dog food (rosemary, gluten, grains)

- Toxic chemicals (household cleaners, pesticides)

- Insect or snake toxins (from stings and bites)

- Portosystemic (liver) shunt

- Brain tumor (malignant or benign)

Diagnosing Seizures in Dogs

If your dog is having a seizure for the first time, call your vet, who will help stabilize your dog if necessary. The next step will be to run diagnostic tests, starting with blood panels (CBC, liver, thyroid) and a physical examination. If initial testing is inconclusive, a veterinary neurologist may run a CT scan, an MRI, or perform a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tap to gather further information on your dog's condition.

Treatment and Prevention

If brain malformations, brain tumors, inflammation in the brain, or liver issues are ruled out, then your dog will likely be diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy and treated with anticonvulsant medication to prevent or reduce seizure occurrence.

Prescription Medications

One or more anticonvulsant medications may be prescribed by your vet to control your dog's seizures:

- Phenobarbital

- Potassium bromide (KBr)

- Primidone

- Imepitoin

- Zonisamide

- Keppra (levetiracetam)

For many dogs, there's a period of trial and error with anticonvulsant therapy. Drugs may be combined, adjusted, or switched until your dog's seizures are regulated. In many cases, lab tests must be performed regularly to monitor your dog's response to medication and overall health.

Prognosis for Dogs With Seizures

Most vets won't initiate pharmaceutical treatment if the seizures occur less than once a month. As with any medication, these drugs have side effects. If they help manage your dog's seizures, you may find that the benefits outweigh the risks. Once medications are started, they are often required for life and must be given at least twice per day. While this is a great responsibility, it can help extend your dog's life. Many dogs with epilepsy live happy, normal lives with infrequent seizures.